Zero Rating, Net Neutrality, and Zuck

Developing countries should "Just Say No" to Facebook's Free Basics program.

Note: This article was originally posted on Medium on Feb.1, 2016.

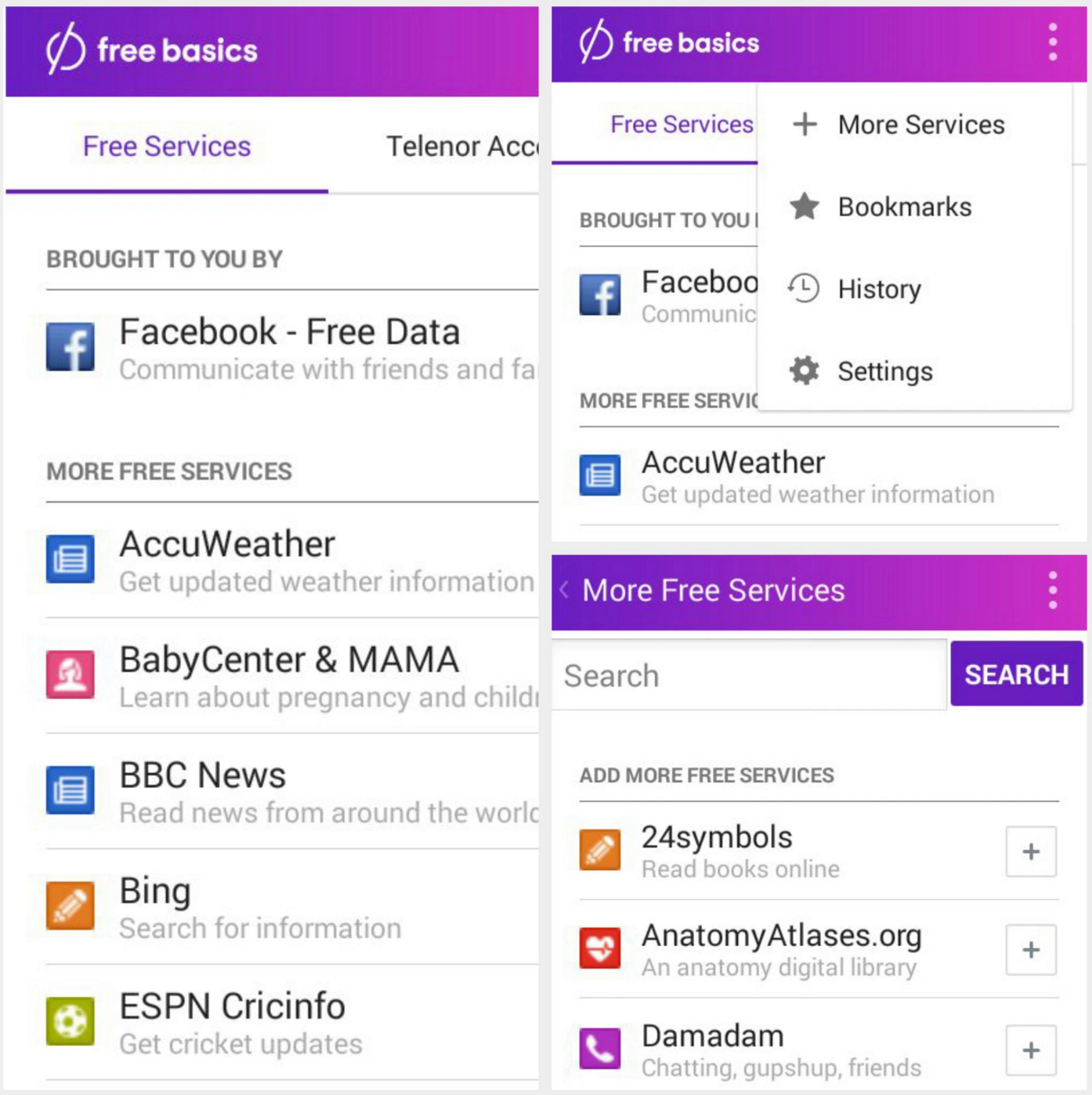

Free Basics by Facebook — previously branded as the Internet.org platform — is a “zero-rated” mobile Internet platform and program for the developing world.

A zero-rated program is one where customers on limited or metered data plans do not get “charged” by Internet service providers for their data usage when accessing certain content, apps, and services. Free Basics, for example, gives its users free access to Facebook, Messenger, and other online services through non-exclusive partnerships with wireless carriers.

Facebook’s push for Free Basics is ostensibly motivated by its desire to help solve the digital divide. However, a huge battle has developed between the company and “net neutrality” activists who oppose the program. The activists argue that Free Basics violates net neutrality principles by creating a “walled garden” Internet experience and is, in truth, a developing markets land grab by Facebook. Facebook argues, to the contrary, that the activists are misguided elites who are depriving the poor of access to vital Internet-delivered services because of a “purist view” of net neutrality.

The debate about Free Basics and net neutrality has been particularly intense in India, with both sides fiercely arguing their points of view to the Indian government and public. In fact, the opposition to Free Basics has been so strong that the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India recently asked Facebook and its wireless carrier partner, Reliance Communications, to suspend the program pending the results of a public consultation process.

The outcome of the Free Basics battle in India could have huge repercussions all over the world. At stake is the answer to whether or not “differential pricing” — which includes zero rating — is an appropriate method for increasing Internet access among those on the wrong side of the digital divide.

But what happens in India could also elucidate how the developed world should handle zero rating, which has turned out to be a hot topic as of late. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission has taken major steps towards enshrining net neutrality principles into the regulatory regime. However, as of today, the Commission has reserved judgment on whether or not zero-rated programs like AT&T’s Sponsored Data, Verizon’s FreeBee, and T-Mobile’s Music Freedom are permissible under net neutrality.

This article will make the following case:

-

It is not clear that all category-based zero rating programs violate net neutrality standards; therefore, such programs should be judged on a case-by-case basis.

-

Facebook’s Free Basics program has morphed into a category-based zero rating program that should be judged on the particulars.

-

A case-specific analysis suggests that Free Basics should not be permitted because of Facebook’s involvement and the danger that poses to competition, diversity in the marketplace, and privacy.

But before we go into the details, we will first have to come to a workable definition of “net neutrality” based on examining what problems the principle is intended to solve.

Defining “Net Neutrality”

The term “net neutrality” is constantly bandied about in the fight over zero rating. Yet, truthfully, there is little clarity amongst the public on what “net neutrality” actually means and what problems the concept is intended to solve.

Fundamentally, what “net neutrality” is really about is making sure that the natural oligopoly positions that Internet service providers (ISPs) typically enjoy are not exploited to give competitive advantages to the content, apps, and services offered either by the ISPs or third party providers. While net neutrality is very much grounded in economic principles supporting competition/anti-trust regulations, the principle is also intended to spur innovation, encourage diversity in the marketplace of ideas, protect digital rights and freedoms, and preserve beneficial Internet standards.

Professor Vishal Misra has written about how the definition of “net neutrality” has evolved over the years. Misra notes that the common folk definition of treating all packets delivered over the Internet equally has never been compatible with the realities of network management. He then argues that the FCC’s recent adoption of net neutrality – which forbids ISPs from blocking or throttling any traffic or implementing paid prioritization (fast lane) schemes – is focused solely on quality of service (QoS) and fails to take into account pricing schemes which do not have QoS effects but do have competitive advantage effects.

Consequently, Misra proposes his own definition, which appears to take into account at least some pricing schemes with competitive advantage effects.

Internet is a platform where ISPs provide no competitive advantage to specific apps/services, either through pricing or QoS #NetNeutrality

— Vishal Misra (@vishalmisra) August 12, 2015

Professor Misra’s self-worded definition of net neutrality. Here is his net neutrality definition, slightly modified for clarity’s sake:

Net neutrality requires that the Internet be maintained as a platform where ISPs provide no competitive advantage to specific content, applications, or services, either through pricing or QoS.

Importantly, Professor Misra’s definition allows for differential QoS or pricing, so long as it is administered in a way that does not favor specific content, apps, or services.

For instance, Misra states, “ISPs can prioritize all real time traffic (e.g. all voice or all Video Conference traffic in a provider agnostic way) over all non-real time traffic. Similarly all emergency services or health monitoring apps can be prioritized.” Misra’s definition also “allows creating and differentially pricing entire class[sic] of services.” An ISP could, for example,“create an extremely low latency service and offer it to all games/gamers without discrimination.”

Professor Misra’s net neutrality definition is quite good. In fact, it is perhaps one of the best concise definitions of net neutrality that has yet been proposed. However, it is important to keep in mind that his formulation allows differential treatment between categories of content, apps, and services.

As we shall see, this allowance for category-based differential treatment muddies the waters when it comes to determining whether or not all zero rating is incompatible with net neutrality.

Can Category-Based Zero Rating Be Net Neutral?

Because net neutrality regulations are primarily directed towards keeping specific vendors from benefiting from ISPs’ market positions to gain a competitive advantage, one might argue that category-based differential treatment that is vendor-agnostic should be permissible. However, this is not an uncontroversial proposition.

Let’s suppose, for example, that an ISP decides to offer a “downgraded video” data service at a lower price point than the normal data service. Both services would have similar speeds and data caps, but the “downgraded video” service would be cheaper because the ISP could reduce the costs associated with video traffic congestion by “throttling” the video. Alternatively, instead of creating a cheaper tier of service, the ISP could incentivize use of a “downgraded video” option by not counting “throttled” video towards usage caps — i.e., by zero rating the “downgraded video.”

Would such a program be permissible under net neutrality, since it would be based on application type and, therefore, vendor-agnostic? Isn’t throttling normally forbidden as harmful under net neutrality?

Well, under the Misra definition of net neutrality, such a “downgraded video” service is arguably permissible because of its category-based differential treatment. And the service might even be permissible under the FCC’s Open Internet Order, despite the order’s no-throttling rule.

“Throttling” is defined in the FCC’s order as “impairing or degrading lawful Internet traffic on the basis of Internet content, application, or service, or use of a non-harmful device.” If the proposed service’s intentional slowing of streaming video traffic still results in decent quality video — say DVD-quality versus full HD — then the traffic is arguably neither impaired nor degraded, meaning that unlawful “throttling” may not be occurring.

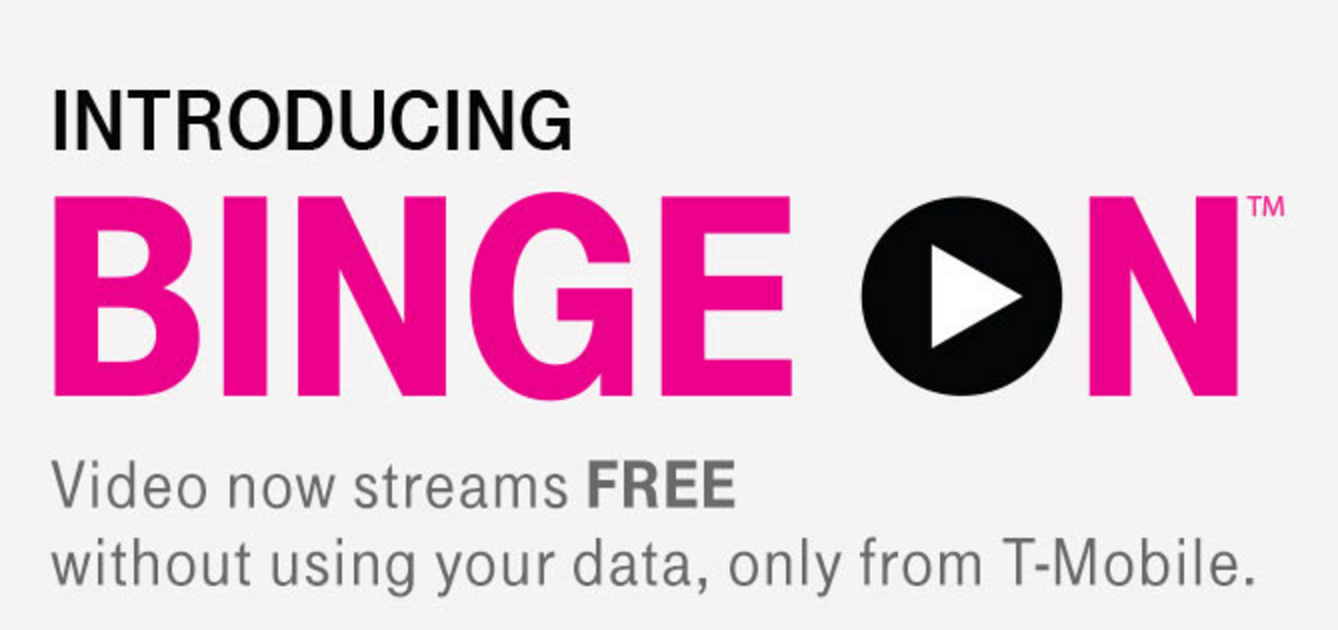

What has been described above is quite similar to T-Mobile’s controversial Binge On program. Binge On is a zero rating program where streaming video content does not count towards a user’s data cap, so long as the service provider’s video stream meets T-Mobile’s technical requirements. Critically, when Binge On is turned on, all streaming video is “throttled” — or “downgraded” if you are marketing the program — and participating content providers’ streams are zero-rated. Theoretically, any content provider can participate in the program at no cost.

So does Binge On violate net neutrality?

On its face, the zero rating program is category-based but vendor-agnostic, therefore appearing to meet the competition-protecting goal of net neutrality. However, Binge On’s technical requirements, which are designed to allow T-Mobile to identify and throttle (or downgrade) streaming video traffic, may inherently produce a disparate impact on certain types of video providers. As Professor Barbara van Schewick has pointed out, for those providers that do not already meet T-Mobile’s requirements, changing the way they deliver video could take significant time and engineering resources. This would “disproportionately affect start-ups, small providers, and non-commercial speakers,” who might be competitively disadvantaged versus larger video content providers until they can actually meet the technical requirements.

Professor van Schewick also argues, contrary to Professor Misra, that ISPs should not be able to engage in category- or class-based differential pricing at all because this would distort “competition among different kinds of applications.” With Binge On, video consumption is made “more appealing than other bandwidth-intensive uses,” and therefore such a program does not comport with net neutrality, according to Professor van Schewick.

It is not entirely clear, however, to what extent “competition” across categories or classes of applications and services actually occurs in the same sense that it occurs between specific applications within a category or class. While data usage for a particular category of application may factor into whether or not a customer with a capped data plan uses that type of application, the substitution of another type of application using less data probably only occurs in some circumstances, if at all.

The upshot of the above is that it is hard to say whether or not there should be a complete ban on category-based zero rating programs. While a program like Binge On raises a number of net neutrality issues, it might not violate net neutrality in all of its possible instantiations.

Therefore, case-by-case analysis of category-based zero rating, rather than outright bans, would appear to be appropriate.

Free Basics and Net Neutrality

Facebook’s current iteration of Free Basics raises the same sorts of net neutrality issues that Binge On does, except even more so.

When Free Basics was first released, the app only included Facebook, Messenger, and a set of basic websites selected by Facebook Inc. This obviously violated net neutrality, as it gave Facebook’s social networking properties and select third party properties a competitive advantage vis a vis those left out. In response to this criticism, Facebook subsequently announced that Free Basics would be restructured into an “open platform,” where any vendor could participate so long as they met certain guidelines.

However, Facebook’s guidelines limit Free Basics to services that do not use VoIP, video, file transfers, high resolution photos, or high volumes of photos, and that “encourage the exploration of the broader internet wherever possible” (a rather ambiguous criterion). Thus, the guidelines effectively result in category-based zero rating, where many different types of Internet-delivered applications and services are excluded.

Facebook argues that the limited nature of Free Basics is mitigated by data indicating that half the people who use the platform to go online for the first time pay to access the full Internet within 30 days. Indeed, the original vision of the program was always as an “on-ramp” to the Internet. (See Zuckerberg’s keynote at Mobile World Congress 2014 below.) Giving free access to “killer apps” like Facebook and Messenger is intended to demonstrate to those on the wrong side of the digital divide why being connected to the Internet is so important.

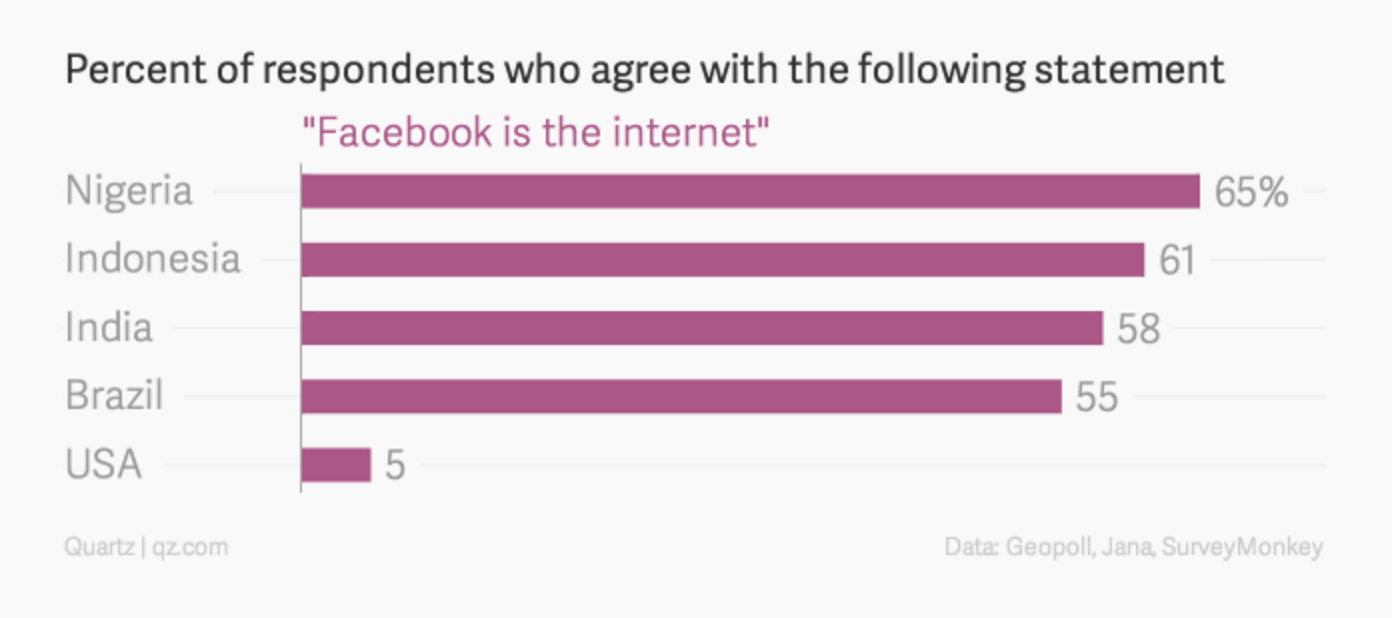

While the on-ramp analogy may hold true, the fact remains that the “basics” stay zero-rated even after a data plan is purchased. And there is evidence indicating that the short periods of time where end users are on-ramped via Facebook-oriented differential pricing plans (see, e.g., Facebook Zero) may result in these users conflating Facebook with the Internet itself.

The rise of mobile operating systems has changed the way that consumers use the Internet, with most new Internet users associating the value of data plans with apps (core OS and third party) rather than the open Web. But the fact that Facebook is viewed by many newbies as the basic social networking application for the mobile Internet is troubling. Indeed, it is the danger of Facebook gaining a permanent competitive advantage versus other social networking companies that makes Free Basics a much more dangerous proposition than if a similar category-based zero rating program were marketed and administered by, say, a Mozilla or Wikimedia.

So, assuming that we are correct to judge category-based zero rating programs on a case-by-case basis, we should explore why Free Basics in particular may be too dangerous to allow if we care about consumers’ long run welfare in developing markets.

Commercial Interests, Network Effects, and First Mover Advantages

One of the major arguments that Facebook has made in its aggressive lobbying campaign for Free Basics is that the program is not about Facebook’s commercial interests. Here is Mark Zuckerberg defending the program in a Times of India op-ed:

This isn’t about Facebook’s commercial interests — there aren’t even any ads in the version of Facebook in Free Basics.

This statement should raise eyebrows. Equating an absence of ads in Free Basics’ stripped-down version of Facebook with a non-commercial interest makes little sense. After all, Facebook itself started as an ad-free service, but it eventually monetized its rapidly growing user base in multiple ways (including ads) that turned out to be very profitable. There is no reason to believe that Facebook will not be able to monetize the users it collects through Free Basics.

Now, there is nothing inherently wrong with Facebook having a commercial interest at play, and we cannot say that Free Basics is all about the company’s commercial interest. Mark Zuckerberg undoubtedly believes that connecting the world to the Internet and to each other via social networking is a very important societal goal, and that Facebook is the best positioned company to do so. He clearly also believes that making profits and increasing social welfare are not mutually exclusive.

So it is a cased of mixed motives for Facebook, which should not be surprising to anyone. In Silicon Valley, it has become de rigueur to argue that organizations with both a social purpose and a profit motive are best positioned to actually achieve progress. Peter Thiel, who happens to be on Facebook’s board, would probably argue that Facebook will be successful in giving people the power to share and making the world more open and connected precisely because it is a mission-oriented company that is profit driven.

But Peter Thiel would also probably predict that Facebook is destined to become a monopoly because it is so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute. And therein lies the problem. Are we really so sure that Facebook Inc. is so great at what it does that no firms can offer services that substitute for Facebook, Messenger, and WhatsApp? Might there be other factors at play that have resulted, or will result, in Facebook’s dominance?

A hallmark of Facebook’s social networking services is that they benefit very strongly from positive network effects. The more people who use the company’s services, the more valuable these services become, and Facebook has benefited from a positive feedback loop that has made its services dominant in many markets. Some would even say that Facebook has become a winner-takes-all company due to these network effects.

Nobody can blame Facebook for marketing services that have positive network effects. However, Facebook’s zero rating efforts give the company a baked-in first mover advantage by making its services the de facto over-the-top social networking apps for participating users. And that should give one pause because that means that Facebook and Messenger could win by default, not because they are so much better than other social networking services.

There is a chance, however slight, that new or existing social networking service providers could effectively compete with Facebook in the markets where Free Basics is being pushed. (Realistically, though, Facebook could easily win on the merits because of the positive network effects and economies of scale that it already enjoys, not to mention its deep pockets and engineering/design talent.) That competition probably ought to occur on a playing field where “free” is the zero-bound for pricing. With Free Basics and Facebook’s other zero rating efforts, the company’s services become better than free, and the resultant competitive advantage could become insurmountable for competitors.

And that is exactly the type of harm that net neutrality is intended to prevent.

Strike one for Free Basics.

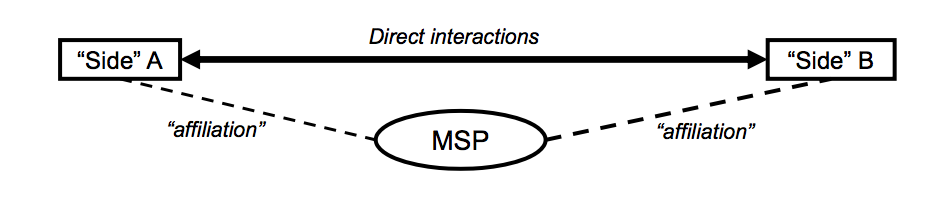

Multi-Sided Platforms and Algorithmic Surfacing

Another thing to consider is that Facebook’s various services are, or are becoming, multi-sided platforms, facilitating interactions between end users and various commercial entities (advertisers, software developers, news outfits, small businesses, etc.). As Professor Andrei Hagiu, whose research focuses on multi-sided platforms (MSPs), notes:

Successful MSPs create enormous value by reducing search costs or transaction costs (or both) for participants. As a result, MSPs often occupy privileged positions in their respective industries; most other industry participants revolve around and depend on MSPs in important ways. (Emphasis added)

MSPs benefit from cross-side network effects; the value to customers on one side of the platform increases with the number of participating customers on another side. Consequently, once an MSP reaches critical mass, high barriers to entry may be created.

Facebook and Messenger, the two Facebook properties included in Free Basics, are leveraging their strengths as social networking services to become very strong MSPs. Messenger, in particular, has the most potential to become a dominant MSP. Messenger, which started out as a simple text messaging service, now serves as an app platform, connects users to services like Uber, gives businesses’ customers service reps an alternative way of communicating with customers, and is developing a “concierge” service to compete with AI personal assistants like Siri and Google Now.

Facebook appears to be taking the same approach to Messenger as Tencent has with WeChat, the Chinese messaging app that Connie Chan, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, has described as “a portal, a platform, and even a mobile operating system depending on how you look at it.” Here’s Chan’s description of WeChat:

Along with its basic communication features, WeChat users in China can access services to hail a taxi, order food delivery, buy movie tickets, play casual games, check in for a flight, send money to friends, access fitness tracker data, book a doctor appointment, get banking statements, pay the water bill, find geo-targeted coupons, recognize music, search for a book at the local library, meet strangers around you, follow celebrity news, read magazine articles, and even donate to charity…all in a single, integrated app.

Chan’s entire post is worth reading to get a sense of what Messenger could potentially become in places like India where the mobile Internet is already king.

While the basic versions of Facebook and Messenger accessible through Free Basics probably will never include all of the features described above, users are still being on-boarded into Facebook Inc.’s mobile MSPs at a price better than free. Given the difficulty of displacing MSPs once they reach critical mass, it would seem foolhardy to allowing a zero rating program that prominently pushes Facebook’s social networking services.

It is also worth noting that a Facebook victory in the messaging MSP battle could be particularly consequential because of the way that Facebook increasingly algorithmically surfaces content. Facebook, perhaps more so than any other company, is intent on tracking user behavior, habits, and preferences — not just on its properties but across the web — in order to serve personalized content to its users.

Personalization is not a bad thing at all; it can be very useful in many circumstances. However, it has to be emphasized that an important goal of net neutrality is to encourage diversity in the marketplace, and the type of personalization that could occur through a dominant Facebook-controlled messaging MSP could easily contravene this goal.

Based on the above, Free Basics gets another strike.

Facebook and Privacy

The last thing to consider is the effect that Facebook’s push for Free Basics could have on the privacy of all users in those specific markets.

It is no secret that Facebook has a history of pushing the boundaries when it comes to privacy, not only for its users but also for non-users who run into Facebook’s Like button (and soon-to-be Reactions?) all across the Internet. Going into all the reasons why privacy matters is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that it is a very important value (or set of values) that could be undermined by Facebook’s plans for Free Basics.

When Mark Zuckerberg discussed the Internet.org initiative at Mobile World Congress 2014, he talked about how it would entail deep integration between Facebook and partner ISPs:

All of the different [free] services that we talked about, with all of the different kinds of up-sells and things that we think that we have the ability to do if we work with a carrier deeply and plug into their systems deeply to make all these flows really efficient and use all the knowledge that we have about customers that both we and the carrier have. (Emphasis added)

In other words, it appears that Zuckerberg’s long-term vision for developing markets ultimately includes Facebook providing retail and behavioral targeting infrastructure to ISPs in some form or fashion. This would allow Facebook and its ISP partners to determine what types of products or services any particular end user would like at any given time based on what is known about that user. The payoff for Facebook might be a cut of the proceeds, whether from sales, ad revenue, or payment fees.

Such tight integration between Facebook and ISPs could bode very ill for privacy in developing markets. And Free Basics appears to be the first step in making that integration possible. Indeed, all Free Basics traffic goes through Facebook servers, though it is not entirely clear why this must be the case for the zero rating to work.

Strike three for Free Basics.

Conclusion

Solving the digital divide, both in developing and developed markets, is hugely important, given the immense benefits that accrue to individuals from being connected to the Internet.

However, given all the dangers detailed above — which result primarily from Facebook’s involvement in Free Basics—and the existence of potentially superior alternatives for solving the problem, authorities in developing markets probably should not permit Free Basics in its current instantiation.